Reprint from illinoispolicy.org

By Bryant Jackson-Green, Dianna Muldrow, Derek Cohen

Download Report

In most of the U.S., states are experiencing a dramatic decline in both crime and incarceration rates. Thirty-two states saw a decrease in both factors simultaneously between 2008 and 2013, according to a report by Pew Charitable Trusts – a positive sign for society. But unfortunately, Illinois was not one of these states. While Illinois’ crime rate dropped by 23 percent from 2008 to 2013, the state’s incarceration rate actually increased by 7 percent over that same period.1

What’s causing Illinois to lag behind? Outdated criminal-justice policies in dire need of reform.

A successful corrections program helps reform offenders so they can complete their sentences and become productive members of society. But too often, prisons are regarded as a place to warehouse offenders instead of rehabilitating them. In Illinois, an indicator of this is the sobering statistic that nearly half of those who are imprisoned will return within three years.2

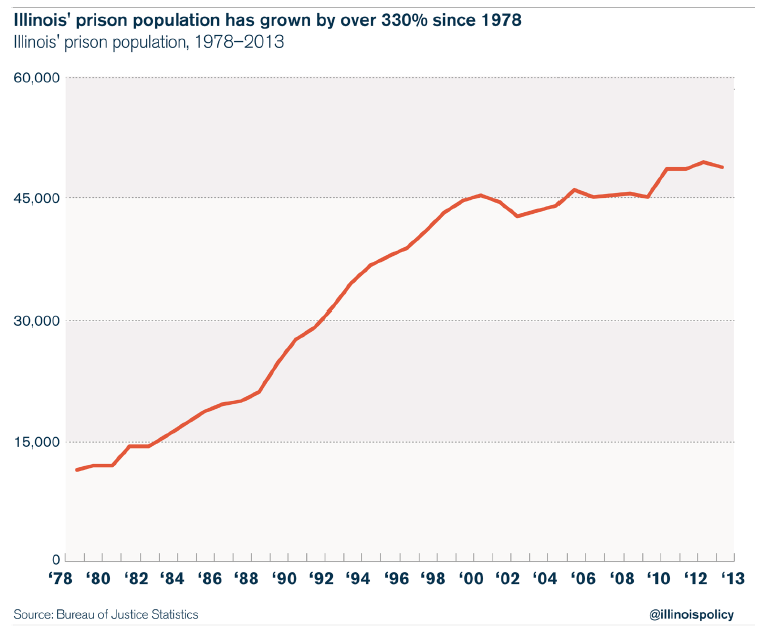

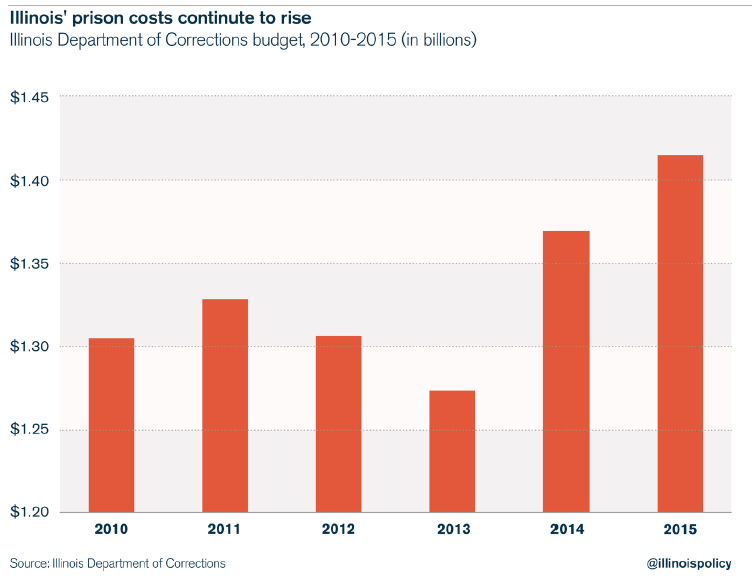

Illinois’ prison costs are directly related to the growth of the prison population. The state’s prison population has increased by more than 330 percent since the 1970s and, as a result, the state’s prisons are now at 150 percent of operational capacity.3 At the same time, spending in the Illinois Department of Corrections is at an all-time high. In fiscal year 2015, the state spent $1.4 billion on its corrections program – an increase of over $184 million since 2007.4

It doesn’t have to be this way. With policy and legislative changes, Illinois can achieve the goal of a lower crime rate, lower incarceration rate and smarter spending on criminal justice while maintaining public safety. The key is focusing on rehabilitation and recovery, not just punishment and putting people behind bars.

Changes need to be made in three general areas:

- Treat the root causes of crime: Illinois needs to divert more offenders into programs that directly target the underlying issues leading them to break the law. These programs, including drug treatment and early-supervised release, not only cost thousands of dollars less per person than prison, but have a proven track record of rehabilitating offenders.

- Lower recidivism: Too many former inmates are returning to Illinois prisons because they have not been re-acclimated to society, and because the law has made it more difficult for them to find legitimate work. Parole and occupational-licensing reform can help ensure ex-offenders stay out of prison once they are back in society.

- Reduce unnecessarily punitive sentences: Illinois needs to make it harder for low-level offenders to end up in prison in the first place.

The following six policy proposals will advance those goals:

1. Expand Adult Redeploy: This report estimates Illinois could save $27 million annually by expanding its diversion program.

2. Establish a restorative-justice program: Illinois should pilot a victim-offender mediation program for property crimes. This could save $780,500 in one year and, if successful and expanded, millions more in later years.

3. Eliminate “max-outs”: To help encourage successful transition back into society, Illinois should allow offenders to trade more time under mandatory supervised release for less time during the final year of their prison sentence. Illinois could potentially save $40 million a year by implementing this reform.

4. Reclassify nonviolent drug offenses: Illinois should follow Utah, South Carolina and other states in making low-level drug possession a misdemeanor instead of a felony. This could potentially save the state nearly $40 million a year.

5. Remove occupational-licensing restrictions: By removing legal barriers to employment, Illinois can create economic opportunity for ex-offenders and earn more in tax revenue.

6. Raise felony thresholds: By raising the felony theft threshold to $1,000 and revisiting it annually, or by pegging it to inflation, this report estimates Illinois can save over $1.5 million a year.5

Introduction

For all the taxpayer money put into corrections, are Illinois residents getting much of a return on their investment?

Illinois operates 25 adult correctional facilities that are only supposed to hold 32,075 inmates.6 But Illinois prisons are severely overcrowded, holding 48,887 inmates at the end of fiscal year 2013. This means state prisons are operating at over 150 percent capacity.7 This is not a recent development. Illinois’ prison population has been on a sharp and steady upward trend for decades, increasing more than sevenfold since the mid-1970s.

Without serious changes, these increases are expected to continue. The Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council, or SPAC, estimates the state prison population will increase by 6,573 inmates over the next 10 years to reach a total of 55,450, based on Illinois Department of Corrections, or IDOC, data.8 Illinois’ financial insolvency – including a $111 billion unfunded pension liability – means spending millions constructing and operating more prisons is not a feasible solution for prison overcrowding.9

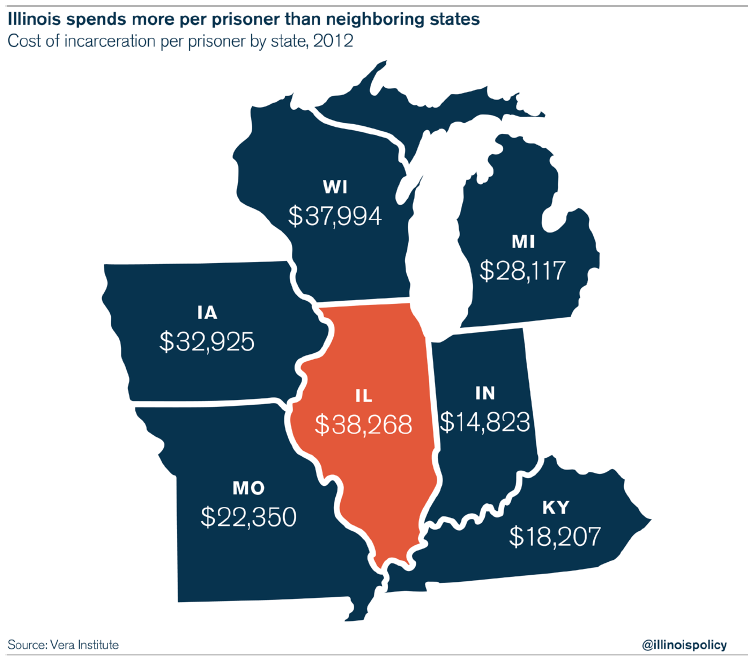

The root of the growth in the prison population can be attributed to a growth in prison admissions, reduced sentencing credit, increased length of prison sentences and a consistently high rate of recidivism, or the percentage of the population that returns to prison after being released. All this has led to Illinois leading the Midwest – and much of the country – in expenditures per inmate.

The Illinois Department of Corrections, or IDOC, directly pays about $21,600 per inmate, largely from the general funds budget. But when costs falling outside of the system – including employee health care, employee benefits, pensions and capital expenses – are factored in, the total raises to $38,268, according the Vera Institute, a nonpartisan criminal-justice research foundation. In Illinois, 32.5 percent of the cost of corrections actually comes from spending outside of the IDOC budget. Of the 40 states included in the Vera Institute’s 2012 study of corrections costs that fall outside of the system, only Connecticut had more corrections expenses fall outside of their state-level prison budget than Illinois.10

Because an unprecedented number of people are serving prison terms, this trend will continue – unless Illinois makes significant policy changes.

Policy Challenges

Growing budgets

The Illinois Department of Corrections, or IDOC, is the state-level agency tasked with running prisons. Inmates are sent to IDOC after they have been convicted of a felony offense by a court. Jails, on the other hand, are short-term facilities where offenders are held after they are arrested and awaiting trial, or serving time for misdemeanors when their sentence lasts for less than a year.11 Local units of government, usually counties, run jail systems. Finally, federal prisons hold inmates serving time for violations of federal law. This paper address state-level spending on prisons, specifically.

In recent years, the IDOC budget has continued to increase despite attempts to bring it under control. The vast majority of the budget is drawn from Illinois’ general fund, with other state funds providing anywhere between $84 million to over $118 million in recent years.12,13 Just since 2010, IDOC’s budget has grown by just under $110 million.

The bulk of IDOC’s spending, more than $1 billion each year, goes toward facility operations – the cost of running state prisons, adult transition centers and work camps. Health-care services follow, costing around $130 million annually. Much less is spent, in comparison, on job-training programs, parole monitoring and substance-abuse treatment regimes.14 Because operations spending makes up the bulk of IDOC’s budget, policy solutions will need to focus on spending in this sector especially.

This is not to suggest significant waste cannot be weeded out of IDOC’s budget to obtain savings. Like any other public agency, IDOC can certainly benefit from using resources more efficiently. While this report does not address these issues, some of the challenges specific to the department are discussed in its 2014 audit from the Illinois auditor general, such as compensatory pay being accrued and doled out in violation of union agreements and federal law.15

Because Illinois’ prison population is so large, the state is unsurprisingly making significant expenditures on prison staffing. IDOC employs nearly 11,000 employees, of which 7,994 are corrections officers – providing for six inmates to an officer.16 IDOC spent $873 million on payroll in 2014.17 However, given the growing inmate population, IDOC has had to increasingly rely on overtime shifts to manage its facilities. State law mandates employees must be paid one and a half times their hourly wage whenever they work overtime, so it should be relied on sparingly. Yet the amount Illinois prisons spend on overtime has spiked by 200 percent since 2004 – and cost taxpayers $74 million in 2014.18 Indeed, it is no surprise then that IDOC has the second-largest salary expenditure of any state agency.19 Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner has proposed hiring 473 additional corrections officers to offset the growth in overtime hours.20 While this may be a successful tactic in the short term, it is unclear whether the long-term costs of new hires – who will accrue raises, receive employee benefits and put more pressure on an already underfunded pension system – would be as cost-effective several years in the future. Still, there may be a good case for increased hiring on some level. The bottom line is that a reliance on overtime raises fiscal concerns, as well as concerns for the safety of prison staff and inmates.

Despite increases in spending, IDOC has made some budget cuts. The largest budgetary decrease came in 2013, when Illinois shut down two prisons, the Tamms Correctional Center and Dwight Correctional Center, along with adult transition centers in Decatur, Carbondale and Chicago.21 However, in 2014, the prison budget jumped higher than the 2012 total, suggesting that the facility closures by themselves failed to address the true driver of prison costs – population growth.

What is driving Illinois’ prison-population growth?

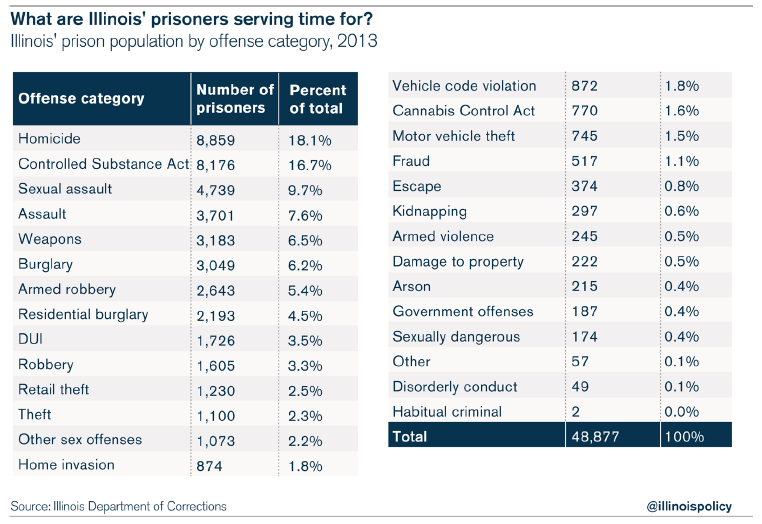

The largest category of offenses in Illinois is drug crimes – 18.3 percent Illinois’ incarcerated are serving time for violations of either the Controlled Substance Act or the Cannabis Control Act. Homicide convictions make up 18.1 percent of the prison population, followed by sexual assaults at 9.7 percent.

When looking at the Illinois prison population as a whole, 50 percent of Illinois inmates are serving time for nonviolent offenses.22 Aside from drug crimes, this includes offenses such as theft, retail theft, burglary and fraud. While these crimes merit an effective response by the state’s criminal-justice system, prison may not be the most effective punishment.

How well is the state doing at rehabilitating offenders, so that when they are released they do not end up making the same mistakes? Illinois’ recidivism rate, which captures how many people fall back into crime within three years after leaving prison, was found by Pew in a national survey to be nearly 52 percent through most of the last decade, meaning more than 5 in 10 offenders who were released from prison returned within the next three years. This was well above the national average of 43 percent.23

Given the state’s budgetary difficulties and the rehabilitative failures of Illinois’ current system, reform is no longer optional. The state’s policy aims should be to incarcerate fewer people for nonviolent offenses and make sure offenders are properly equipped so that when they leave to re-enter society, they will be much less likely to return.

Recommendations

The state’s criminal-justice budget is overgrown and, without intervention, promises to continue its upward trajectory. Getting costs under control will require significant changes in the coming years. The recommendations below are first-step proposals to relieve stresses on the state’s criminal-justice system.

In the next 10 years the state’s prison population will increase by 6,573 inmates to reach a total of 55,450, according to estimates from the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council, or SPAC, based on Illinois Department of Corrections, or IDOC, data.24

According to the data analyzed by the SPAC, there are two main drivers behind Illinois’ rising prison numbers. First, prison admissions have increased as more offenses have become felonies and the persistently high recidivism rate shows that offenders keep returning to prison. Second, the average lengths of sentences have increased, largely as a result of truth-in-sentencing laws, mandatory minimums and a reduction in sentencing credit for good behavior.25 The recommendations below target these drivers.

While this evaluation does not look at costs that would be incurred were Illinois to construct new prisons, the fact that prisons currently operate at over 150 percent capacity makes this an extremely likely possibility in the next decade – if reform is neglected. Illinois already faces a massive debt crisis, with unfunded pension liabilities topping $111 billion.26 The state simply cannot afford new prison construction. Operating over capacity also runs the risk of legal intervention by the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2011, when California’s prisons were operating at around 180 percent capacity, the court ordered the state to reduce its prison population on the grounds that the conditions created by overcrowding violated inmates’ Eighth Amendment right against cruel and unusual punishment.27 Action should be taken immediately to prevent a similar outcome in Illinois.

Other states that have implemented reforms have seen significant savings. Over the last several years, Texas has been able to avoid over $3 billion in expected costs by decreasing its inmate population and closing prisons.28 Pennsylvania recently began to enact many of these reforms and is predicted to save $250 million dollars.29 Illinois can also experience these benefits, but it must first take steps toward reform, including the six policy recommendations that follow.

1. Expansion of Adult Redeploy

Adult Redeploy is a state-administered program that provides funding incentives for counties to create alternative programs, such as drug or mental-health treatment, where nonviolent offenders can receive targeted care instead of going to state prison.30

The rationale behind the program is straightforward: by investing money in community corrections that treat the drug or mental-health challenges of prospective inmates, the state can avoid more costly expenditures on prison. The goals for the program are measured by reduced prison overcrowding, lowered cost to taxpayers and decreased recidivism rates.31 Once a county has reached these goals they are awarded a portion of the savings from the state. This new funding is then reinvested in strengthening alternatives to prison and further reducing recidivism.

The Adult Redeploy program is currently funded by annual appropriations from the state’s General Revenue Fund through the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. It began as a pilot program in 2010, through a combination of state funding and a federal grant from the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program, which ended in 2013. After that, Illinois devoted $2 million for the program in fiscal year 2013 and $7 million in fiscal year 2014.32

The Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority announced on Feb. 17, 2015, that the program saved corrections an estimated $46.8 million between January 2011 and December 2014 by diverting 2,025 nonviolent offenders who would have otherwise served time in state prison.33

Adult Redeploy is optional, but has been enacted in 39 of the 102 counties in Illinois, including Cook County.34 Illinois should continue to incentivize other counties to join. Although the introduction of small counties with low population densities would make less of an impact toward reducing the state’s prison population, there are still 63 other counties that have yet to join; Illinois should make every effort to enroll each one.

Despite the program’s promise, there are aspects of Adult Redeploy that need to be expanded and improved across the board. In 2010, even after Adult Redeploy was launched, 29 percent of Illinois’ prison admissions were returning technical parole violators.35 Technical parole violators are offenders who return to prison because they have broken a condition of their parole, such as missing a check-in with their parole officer or being unable to find housing consistent with their parole requirements. The seriousness of these violations varies greatly case by case. By definition, however, these violators have not committed a new crime.

When thinking of parole generally, graduated sanctions provide parole and probation officers with alternative methods to deal with condition violations. Instead of immediate re-incarceration, the parole officer can use other means, incrementally increasing consequences as necessary. Electronic monitoring devices and a decreased area of mobility could be used progressively; overnight stays in jail or weekends of confinement are other tools to consider. One promising approach to parole reform is the Honest Opportunity Probation Enforcement, or HOPE, court model. It approaches violations of parole by responding with swift and certain sanctions to address violations, rather than far-off court dates and minor slaps on the wrist. For example, every time a probationer breaks a rule, such as missing a check in with their supervisor, they are immediately sentenced to a short stay in county jail. Checking in with supervisors is much more frequent as well – in the Hawaii HOPE court program, offenders must check in daily and report for random drug testing.36

Naturally, the appropriate punishment depends on the circumstances of the offense. A nonviolent offender who was late for a meeting or had a dirty urine sample would be a less likely candidate to be sent to prison. On the other hand, common-sense sanctions still need to be applied in potentially dangerous situations, such as when a former sex offender violates location restrictions by entering school property. Public safety must come first, but Illinois should still make every effort to use graduated sanctions.

Use of risk-needs assessments would be useful in forwarding public-safety goals. After an offender is placed on supervision, an assessment should be made using an evidence-based tool. This will help inform the parole or probation officer of the appropriate response to violations. Knowing when an offender is more likely to recidivate would help corrections officials reduce the risk of program participants committing new crimes.

Another limit on the Adult Redeploy program is that persons convicted of violent offenses are ineligible for participation in Redeploy-funded diversion programs. The Illinois Crime Reduction Act of 2009, which established the program, explicitly excludes violent offenders from the program, but there should be a way for them to gain eligibility.37 After all, though nearly half of Illinois offenders are serving time for nonviolent crimes, nearly all offenders, regardless of what their original offense was, will eventually have to be released. Mental-health problems and drug addiction are not struggles that only nonviolent offenders face, so Illinois’ rehabilitative diversion programs should not focus exclusively on nonviolent offenders. This would require making some distinctions between types of violent offenders and the circumstances of their crime. Someone who made threats while carrying out an unarmed robbery does not pose the same public-safety risk as someone who committed sexual assault. Of course, some restrictions are reasonable – but they should be targeted toward specific offenses, not simply to violent crimes generally. Categorical bars are too broad. Illinois should be able to tailor the Crime Reduction Act to exclude the most dangerous violent offenders, while diverting first-time offenders with demonstrated substance-abuse or mental-health problems, even if this comes after spending some time in a jail or prison.

Illinois should continue to incentivize all counties to engage in Adult Redeploy, and specifically encourage those already engaged to lower the number of technical and misdemeanor revocations among offenders on probation or parole. Since immediate revocation is not necessary for these offenses, implementing a graduated sanctions program will allow parole and probation officers to enforce the conditions of supervision, without returning the offender to high-cost facilities. The incentives provided by the program have worked well for the state but could be improved upon by adopting these recommendations.

Estimated savings:

According to the three years’ worth of data garnered from the Adult Redeploy program in Illinois, savings have increased every year.38 In 2011, the state reaped almost $3 million worth of savings that would have otherwise been devoted to a larger prison population. In 2012, the state saved an estimated $13 million. In 2013, the last year in which a report was issued, the state had saved more than an estimated total of $27 million. By the end of 2014, 2,025 nonviolent offenders had been diverted from Illinois prisons, and the program saved Illinois up to $46.8 million.39

Exactly how much Illinois saves from diversion depends on how long of a prison term offenders would otherwise serve. The average annual marginal cost of incarceration is $5,961 whereas intervention through Adult Redeploy only costs $4,400 per participant. Thus, there would be instant savings of $1,561 for every person diverted from Illinois’ prison population. This report assumes that participants would have served approximately one year in prison, since this is usually the minimum sentence for any felony conviction (although it varies when offenders get credit for time served in jail; at the same time, they may be serving terms greater than a year, in which case savings will be greater than the estimate provided here).40 According to the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, there are approximately 13,000 average annual admissions to IDOC who appear eligible for Adult Redeploy programs.41 If Illinois could manage to serve at least 25 percent more people than it did in 2013 – 1,594 offenders total – the state could save at least $2,488,234 in marginal costs in 2016, and potentially up to $27,416,800 if administrative costs fall proportionally with the prison population. Encouraging other counties to participate, refining the handling of technical violators, and expanding participation eligibility will only increase state savings in future years.

2. Adult restorative justice

Another cost-savings project that should be established in Illinois is an adult restorative-justice program.42 Restorative justice is a program usually aimed at nonviolent property crimes that brings victims together with penitent offenders, and allows victims to voice their concerns and pain.43 Most programs are contingent on willing participation of both the defendant and the victim, as well as either the admission of guilt or – more rarely – the finding of guilt for the defendant. If both parties are willing, the process begins with a conference between the two. Victims are given an opportunity to discuss how the offender’s action harmed them specifically. Through discussions the victim is able to determine the sanctions they think are appropriate, such as compensation for damages, community service or volunteering at the charity of their choice. Research has shown higher rates of victim satisfaction after completing a restorative-justice program than through trials resulting in incarceration.44

Another key function of restorative justice is that it requires the defendant to accept responsibility for their actions. The process does not continue if the defendant does not clearly acknowledge responsibility for the harm he or she caused throughout the process and show signs of remorse. Having the offender acknowledge his or her wrongdoing can be very helpful for victims. Defendants that attempt to excuse their behavior or place blame elsewhere are unlikely to be able to complete the program.45

Restorative justice does not ignore the responsibility that the offender has to the community at large. Frequently, restorative-justice programs have a mandatory community-service requirement. This allows the offender to acknowledge that they injured both an individual and the public by breaking the law, and make amends for their crime through service.46

Currently, Illinois has very limited restorative-justice programming for juveniles, provided by the Juvenile Court Act.47 The state should introduce the option of restorative-justice programming for adults. Bringing victims into the process is proven to improve their results, lower recidivism and reduce costs. All of these would benefit Illinois’ overcrowded criminal justice system.

Estimated savings:

Restorative-justice programs have been implemented very slowly across the nation. Because of their scattered and limited nature, as well as their very individualized formation, the cost benefit has been difficult to estimate. However, other states have programs and have shown there are significant savings in cost and lowered recidivism.

Restorative-justice programs save money in various ways. Bridges to Life, a Texas program, is a 12-week course for offenders currently serving their time in incarceration.48 The program – which has provided services to 3,100 offenders – is a faith-based program that encourages interaction between offenders and victims. The intent is to better serve victims and promote their peace of mind and to lower recidivism rates. Established in 1998, the program has been successful so far, lowering recidivism rates down to 18.6 percent after three years, much lower than the national average of 38 percent to 40 percent. It is difficult to make cost-saving estimates from possible recidivism reduction, but estimates range in the millions.49

This report proposes a trial program to determine whether this program can also be as successful in Illinois. The trial program could be run under Adult Redeploy or provided for under a separate statute. Illinois could start by diverting a small number of property offenders, perhaps around 500, convicted of offenses such as retail theft or burglary. Eligibility would be contingent on the victim’s consent to participate. Offenders would, first and foremost, be responsible for compensating their victims for the loss, pain and suffering their actions have caused. This report assumes such a program could be run for the same cost, and likely less, than the cost of the average Adult Redeploy intervention, or about $4,400 per participant. Since the marginal cost of prison is $5,961, Illinois could save $1,561 per participant. Assuming also that the property offenders would have served around one year in prison otherwise, Illinois could save $780,500. It would be important to then monitor the recidivism rates of program participants, and to track the satisfaction of victims who participated. If successful, the program could be expanded and may eventually save the state millions in avoided prison costs.

Other recidivism programs provide front-end alternative options specifically tailored for low-level property offenders, juveniles, family offenses and many others.50 Illinois can tailor its program as the state chooses.

3. Eliminate “max-outs”

Increased sentence length and truth-in-sentencing movements have contributed to the rise of offenders “maxing-out” of their sentences. Maxing-out means that an offender has completed his or her full sentence in prison, and will leave the system without any form of supervision. Research shows that former inmates released without supervision are more likely to struggle and recidivate, often ending up with them being placed in prison once more at taxpayer expense.51

According to IDOC, 4,477 inmates exited Illinois prisons without going onto parole in 2014.52 This number includes individuals who had been on parole before, but were readmitted later for violating parole conditions. There are many reasons why this may have happened, but this doesn’t necessarily mean they committed a new crime – technical parole violators may have simply been unable to secure a housing situation consistent with their parole requirements.

The rise of maxing-out is a difficult question for current inmates whose sentences have already been decided and who are currently doing time. Once a prisoner has served his or her full sentence, it is unconstitutional to force additional supervision. An offender who has served the time that a judge required of them cannot be required to complete a parole period. The offender’s debt to society has been paid, and he or she owes no more without a trial. However, Illinois can offer an alternative to inmates approaching the end of their sentences.

For example, when an inmate has six months left before release, the state can give him the choice of serving the last six months of his sentence in prison, or serving a year of parole. Because this option doubles the length of supervision an inmate will undergo, inmates will have to carefully consider whether they wish to accept the offer. This encourages positive self-selection; inmates who strongly believe they can complete the parole period without committing a violation are more likely to accept the offer. This will increase the safety and success of the program.

Parole provides the supervisory period that allows for a more successful transition to the general community, while still respecting the sentence awarded to the offender. It is important that this is offered as an option instead of a requirement for existing inmates, because it extends their sentence, which would be unconstitutional unless it is voluntary on their part.

It’s important that savings from policy changes be directed toward improving available parole options. In order for parole to be most effective, technical violations and misdemeanor violations should be met with graduated sanctions instead of immediate revocation. Graduated sanctions provide a parole officer with multiple tools to deal with violations immediately, instead of always having to resort to the strongest possible punishment. These sanctions can start small, a curfew or community service, for example, and grow based on the number and severity of infractions. House arrest, increased substance-abuse testing and weekend detention in a facility are all smaller sanctions that strengthen the probation and parole systems without requiring re-incarceration.

Estimated savings:

Given the cost differences between parole and incarceration, there are clear savings involved in cases with increased post-prison supervision. The recommendation above is for voluntary supervision, which would extend the sentence length overall, but at a cheaper cost and with better returns than prison alone. It is unclear how many offenders would opt for this, but a savings number can be estimated per participating offender.

In 2013, Illinois averaged a cost of $21,600 per year to house each incarcerated offender.53 In 2014, the per capita cost of parole was estimated to be just $1,834 a year per offender.54 Following the proposal of exchanging the last six months of a prison sentence in return for a year of mandatory supervised release, the correctional system would save almost $9,000 per participating offender. According to IDOC, 4,477 people exited Illinois prisons directly in 2014, without going on parole. Assuming these individuals could trade 6 months from their prison term for a year on parole, Illinois could potentially save up to $40,140,782.

In looking at the marginal costs of incarceration, one compares the per capita cost of incarceration – $5,961 – with the marginal cost of mandatory supervised release, or parole, which is $510.55 Instead of spending $2,981 on six months of a prison sentence, Illinois would save $2,471 per participant. Assuming the same number of participants as above, that would instantly save Illinois $11,062,667.

4. Reclassifying nonviolent drug offenses

Several states across the country have moved low-level drug possession from a felony classification to a misdemeanor classification. These changes have occurred in both liberal and conservative states. South Carolina, Mississippi and Wyoming are among those that have made the switch.56, 57

Drug addiction is a dangerous and concerning problem. Drug crimes should be a concern of each state and deserve an appropriate response, in order to protect public safety and address harms caused to the community. However, these states are demonstrating that long and expensive stints in jail are not always the most effective way to deal with this problem. Simply housing offenders without addressing their problems does nothing to address the root cause of the offense.

Illinois should join these states and lower nonviolent, low-level drug offenses to misdemeanors. These reforms have not led to increased drug-crime rates in the states that have implemented them, and the savings can be redirected to treatment programs for misdemeanants instead. Illinois spends approximately $21,600 a year to incarcerate an individual. Class 4 felons can be sentenced to prison for one to three years, but average a six-month stay, and are therefore costing the state a little over $10,000 each.58 Were Class 4 drug felonies reclassified to Class A misdemeanors, these offenders would instead be sentenced to a maximum of one year in jail and two years on probation.59 Even assuming that they serve, on average, less time than the maximum (as they currently tend to under the felony law) Illinois can still earn significant savings.

Estimated savings:

If misdemeanor drug offenders continue to average six months on their sentence, but split their time between jail and probation, the state would save several thousand dollars per offender. In 2013, there were 1,835 people serving time for Class 4 felony violations of the Controlled Substances Act. Class 4 felony marijuana possession is not included in this analysis due to pending legislation, passed by the Illinois House and Senate, establishing civil penalties for lower-level marijuana possession.60 This analysis assumes offenders would serve a one-year sentence, the minimum sentence for felony convictions (although time served would vary depending on credit received from jail time and possible credit for good behavior). In terms of marginal costs, IDOC would save $5,961 per offender, or $10,938,435 annually. If administrative costs fall along with the population decrease, this could potentially save IDOC up to $39,363,000 a year.

There would even be savings on the local level with this reform. The state would need to forward some of the savings to local entities now housing the offenders or supervising them. Other savings could be reinvested in community programs and drug treatment. This would help ensure that the numbers of those prosecuted for these offenses would continue to decrease. The annual marginal cost per inmate in jails is just over $15,000, and the annual cost of an inmate’s probation is estimated at $1,800.61 Assuming the offender is still given a six-month sentence, but it is split in half between jail and probation, counties will cut the cost by over half. Savings would total more than $6,000 per offender, and applied retroactively would save over $12 million immediately, given the number of Class 4 felony offenders currently in IDOC.62 Were these offenders to receive only probation for the time period, localities would save over $18 million.

5. Removing occupational-licensing restrictions

A key factor in whether former inmates will recidivate is employment. A previous offender with steady employment is much less likely to return to crime. This is particularly true for skilled positions. The University of Minnesota found in a study that offenders who held skilled jobs – jobs that required training or licensing – were 11 percent less likely to recidivate than former offenders who held low-skill jobs such as food-service positions.63

This is why it is key that Illinois eliminate many of the restrictions it has on licensing for former offenders. Licensed positions are particularly key to lowering recidivism, yet at least 118 state-level licenses either must or may not be granted to former offenders. The state may deny licensure to an ex-offender for professions such as dance-hall operator, geologist, dietitian, roofer and sports agent.64

There may be reason for case-by-case license denials. No one wants to risk allowing a former child molester to teach children in a school, for example, no matter how long ago the original offense occurred. However, most of the licensing restrictions do not have that solid basis or reasoning, nor is the risk even comparable.

Licensing restrictions in Illinois are usually for former felons.65 But this broad dictate does not differentiate between nonviolent felonies and violent felonies. Many licenses do not even set a time period after which the restrictions can be lifted. The restrictions cover a host of positions that do not have a public-safety element. Occupational licensing in general raises barriers to entry that both prevent people from finding employment and unfairly protect an industry’s established players from market competition.66 Tailoring Illinois’ restrictions could still protect positions dealing with vulnerable populations, but would also provide career options that will lower the recidivism rate for the state.

Illinois should first differentiate between nonviolent felons and violent felons, removing the restrictions for nonviolent felons – particularly low-level drug and property offenders – if the position is not related to the offense. Any bans or restrictions that remain should come with a time frame that will eventually allow any ex-offender to apply for a license. Occupations that completely ban felonies should change these restrictions to allow case-by-case decisions. Additionally, the list of occupations that ban or restrict offenders from licenses should be reconsidered and trimmed to remove occupations for which there are no obvious public-safety risks.

Estimated savings:

It would be difficult to estimate the magnitude of the effects on state spending of this reform. The savings that do occur would mostly be preventive – reducing the amount the state spends on prisons since employment drastically reduces the likelihood that ex-offenders will recidivate. Employment barriers are a major obstacle to ex-offenders re-establishing their lives, as the more difficult it is to find stable work, the more likely ex-offenders are to turn to crime for earnings.

It is worth considering how much tax revenue Illinois loses out on while ex-offenders remain shut out of jobs by occupational-licensing laws. For example,the median salary for a barber in Chicago is $30,584.67 Yet haircutting is one of the professions where a license can be denied if an applicant has a criminal record. For every individual who cannot work in this field, Illinois loses about $1,423 in state income-tax revenue.68 Licensed professions tend to allow for higher lifetime earnings for those able to find work. Illinois can’t afford to keep denying opportunities for financial stability and advancement to ex-offenders.

6. Raise felony thresholds

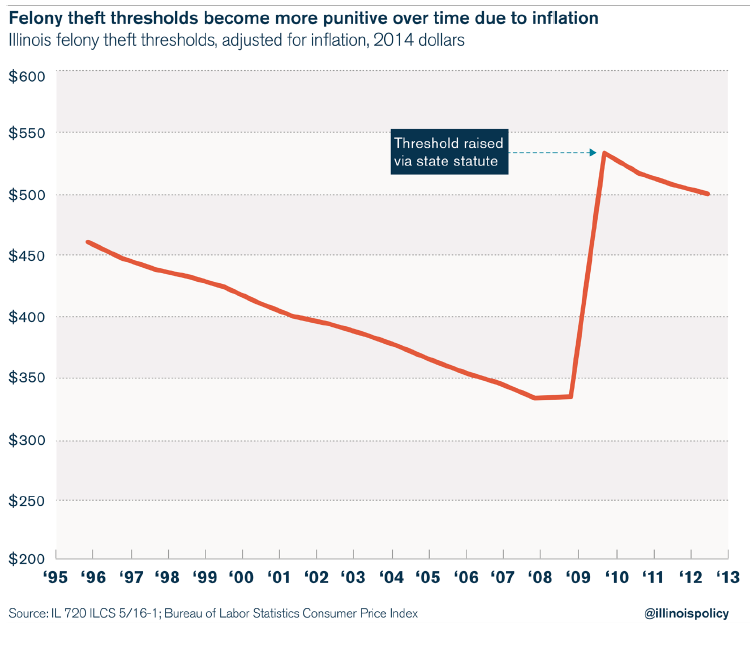

Felony thresholds are specific dollar ranges that match the value of property stolen or destroyed with the severity of the sentence offenders are subject to. Today, the threshold for felony theft inaccurately accounts for the value of goods stolen. Unfortunately, statutorily enshrined felony theft thresholds do not make these adjustments themselves. For example, one range may say that shoplifting in excess of $500 would be a felony, instead of a misdemeanor. However, these dollar amounts are not automatically adjusted for inflation. To that end, Illinois’ Class 4 felony for theft of $500, raised from $300 in 2010, has made the law proportional to the crime committed.69 But as natural inflation persists, the statute will again begin to lose similitude with a proportional punishment.

The figure below illustrates that as the dollar loses value over time, the threshold established in statute becomes more punitive. Low-level offenders exposed to costly felony-level sentences represent an inefficient and ineffective use of prison bed space, and prevent criminals from remunerating their victims.70

The Illinois General Assembly should strongly consider including a provision that would require lawmakers to revisit the valuation contained within the statute on a regular interval, namely including an expiry date in the law. Pegging the threshold to inflation is intellectually defensible, though it presents its own set of difficulties in enforcement and prosecution.

Estimated savings:

If Illinois decides to raise its felony theft thresholds to $1,000, as several other states have done, it could gain significant savings. Given the number of cases that IDOC has under Class 3 felony theft – 254 persons – and the average amount of time that Class 3 felony offenders spend incarcerated – about one year as of 2011– the state could save $1,514,094.71, 72 There are several caveats to the calculation of these savings. The calculations must assume an equal distribution of dollar value in theft from the current range of $500 to $10,000. In reality, there are likely more offenders convicted of lower levels of theft, which would increase the potential savings. It is also important to note that state savings would need to be offset for a possible increase in local-level probation costs, as counties handle punishment for misdemeanor offenses.

California enacted a similar adjustment in Proposition 47. The state raised the felony threshold to $950, lowering lesser offenses to the highest misdemeanor classification. Precise results from this change are not completely clear as yet, but the state’s cash-strapped and overcrowded prison system has experienced serious relief.73 But since lowering the number of felonies could increase the number of offenders being housed by jail systems, it would be important to transfer some of the state savings to jails in order to better equip them to effectively handle the increased population.

Conclusion

The proposals herein are only first steps toward reducing the state’s prison population, continuing to reduce crime and bringing Illinois’ budget under control. As the number of offenders in Illinois’ prisons decrease, and fewer ex-offenders return, it should become possible to make corresponding cuts in administration and staffing. Given the overcrowded state of IDOC facilities, much of the immediate savings will come from avoiding the need to construct new prison facilities – an issue that may arise if Illinois’ inmate population continues to grow at the same rate.

Taxpayers expect Illinois’ criminal-justice system to maintain public safety and respect individual rights while maintaining fiscal integrity. Lawmakers will have to get smart on crime – not simply tough – to meet the corrections challenges Illinois is facing. Focusing single-mindedly on punishment and incarceration got Illinois into its current mess. Investing in rehabilitation and reform not only saves money – it helps create a fairer, more effective justice system Illinoisans can all take pride in.